Is QE Back?

The Dynamics of Quantitative Easing

Is anyone really surprised?

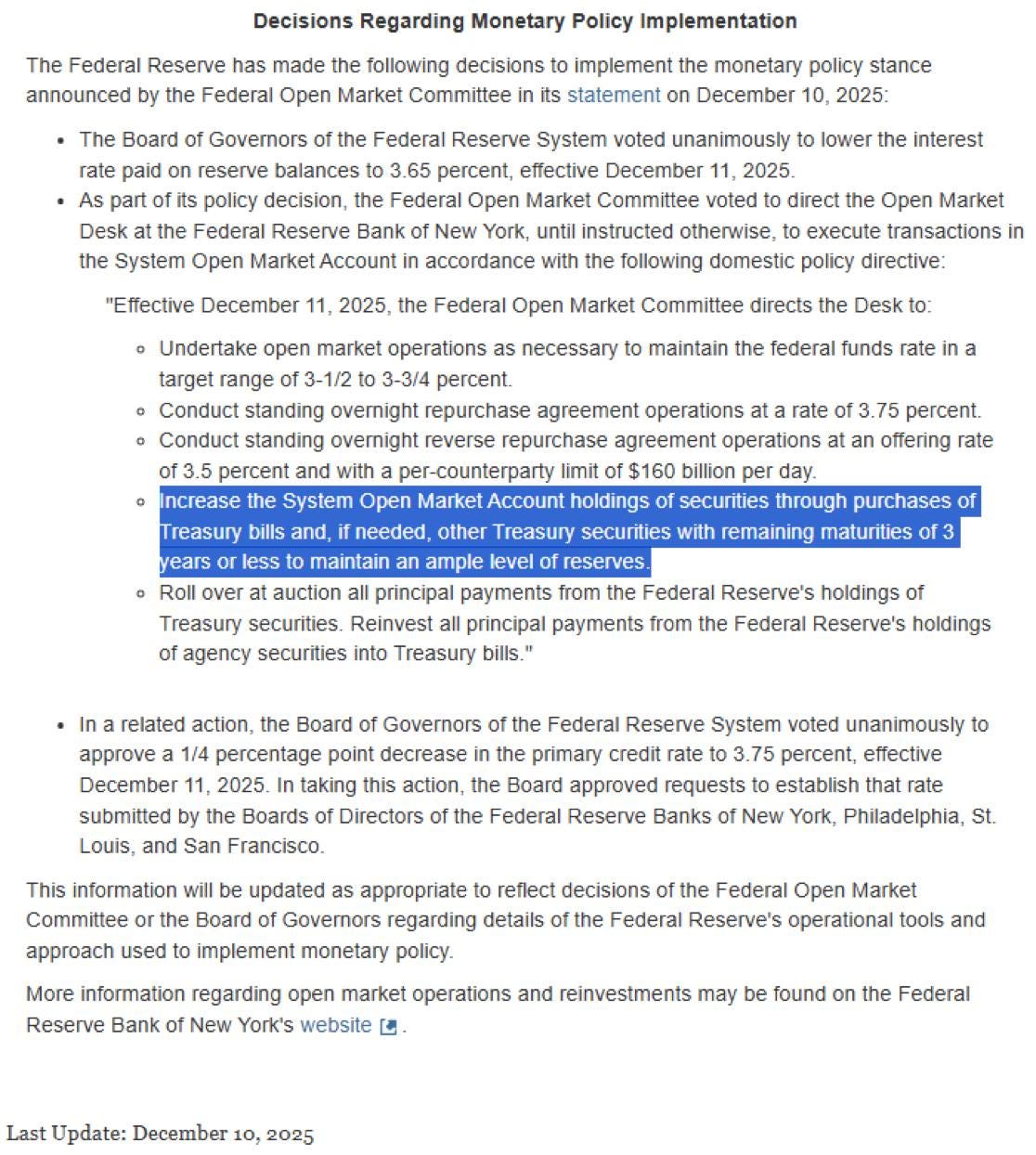

The Fed have finally roundtripped. At the latest FOMC Meeting Powell announced, that the Fed would begin gradually expanding its balance sheet at a pace of $40 billion per month. This marks a notable shift in tone just a couple meetings after Quantitative Tightening was paused and only weeks after persistent stress began to surface in overnight money markets. Under the new plan, the Fed will purchase Treasury securities with maturities of up to three years. Naturally, U.S equities are jubilant as the social media guru’s were quick to exclaim that Quantitative Easing is back.

So is it true? Is QE finally back? Is alt-season finally on the horizon? Well, not quite. The answer to this is far more nuanced that the confident proclamations circulating from Zero Hedge and others. Whilst it is true that yes - balance sheet expansion has technically resumed, this is not quantitative easing in the sense that matters most for asset prices or macroeconomic transmission. Understanding why requires (what this post will aim at) revising how QE actually works and why the maturity of assets the Fed buys is the crucial variable.

“True QE”

Understand that “true” quantitative easing operates through duration extraction.

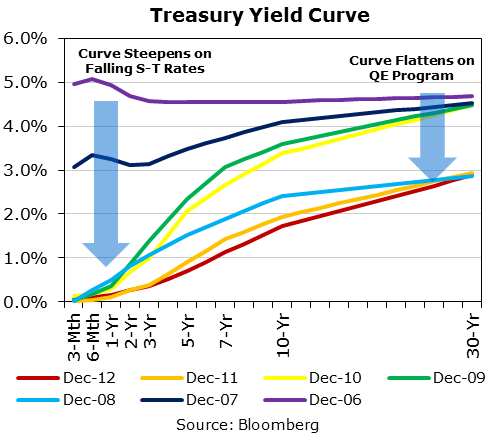

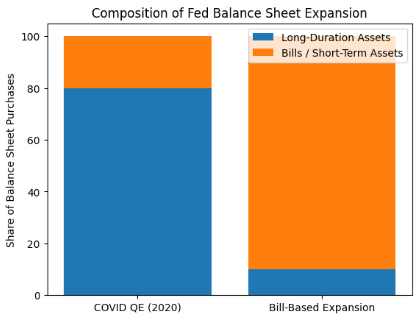

When the Fed purchases long-dated Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, this removes duration risk from private-sector portfolios. Investors and dealers, no longer able to hold that duration, are forced to rebalance into other long-duration assets or into riskier instruments. This process flattens the yield curve, compresses term premia, and lowers borrowing costs across the economy. The macroeconomic consequence from this are a powerful impulse of easing in financial conditions that supports credit creation, asset prices, and growth. This was what we got during COVID and post GFC.

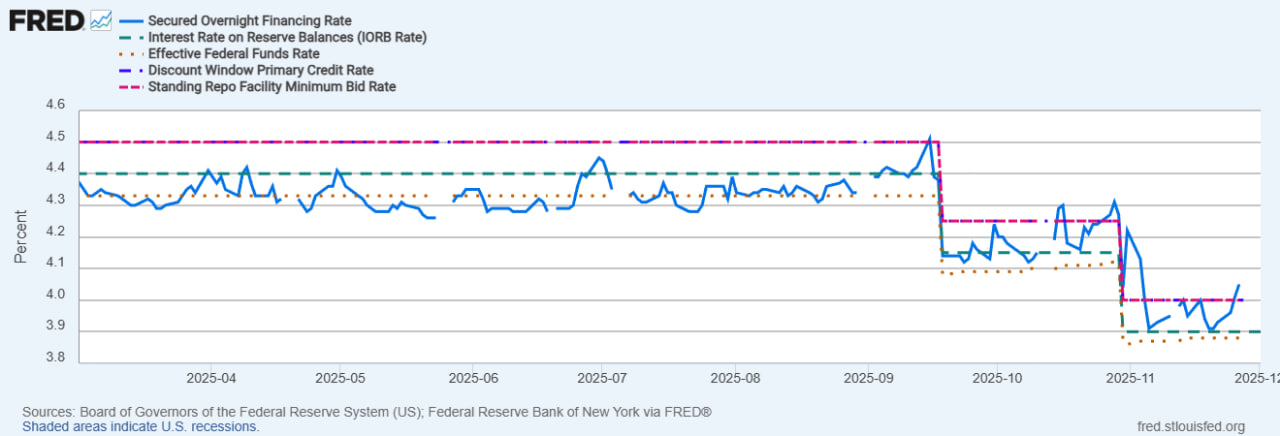

The program announced at the latest FOMC does none of this. By purchasing Treasury bills and short-dated securities out to three years, the Fed is acquiring assets that carry very little duration risk. Swapping bills for reserves is close to a duration-neutral operation. See below how Treasury bills yield roughly the policy rate (EFFR Green), while bank reserves created through these purchases earn interest on reserve balances (Orange) at the policy rate as well. From the perspective of dealers, there is no meaningful incentive to move out the curve. The impact on yields is therefore concentrated at the very front end, with little transmission to longer maturities or broader financial conditions.

In this sense, what the Fed is implementing (on the surface at least) we see to be best described as “QE lite.” It is balance sheet growth, but not the kind that reshapes portfolios or drives investors into risk assets through forced rebalancing. It is liquidity management and mild easing, not the macro-level duration extraction traditionally associated with QE.

The mechanics of the operation are straightforward. When the Fed buys Treasury bills from dealers, the dealers’ securities holdings decline and their reserve balances rise.

Bank reserves are created as the Fed expands its liabilities. Dealers then face a choice about what to do with this additional cash. They can rebuy bills, extend duration by moving into intermediate treasuries, or allocate toward risk assets. The critical distinction is that none of these choices are forced.

Under traditional QE, where the Fed removes vast quantities of long-duration Treasuries from the market, investors are more compelled to hold less duration than they otherwise would. That constraint is what makes the portfolio rebalancing effect so powerful. Bill purchases, by contrast, remove assets that contain almost no duration risk, leaving dealers largely indifferent about reallocating further out the curve. The “push” into risk is therefore much weaker.

The Fed Intervention

Even still, this is technical “balance sheet expansion”. The Fed is increasing its liabilities - so naturally we need to know why this is happening.

Know that the Fed does not engage in so-called “technical” balance sheet injections arbitrarily or during periods of abundant liquidity. These operations are historically only ever deployed when money-market stress is emerging or when policymakers believe it is likely to emerge. The Fed’s focus in these moments is therefore not macroeconomic stimulus, but more aimed at the stability of the financial system’s plumbing.

Earlier in the month we noted that money markets were showing evident signs of stress. Here are some posts from Telegram:

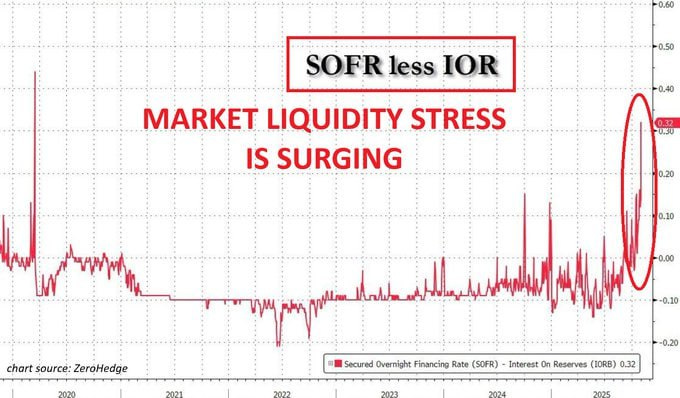

At the beginning of November, we reported that SOFR - IORB spread spiked to 32bps, the highest since 2020.

Similarly, SOFR moved above the SRF rate over November, outside of end of month window dressing for banks.

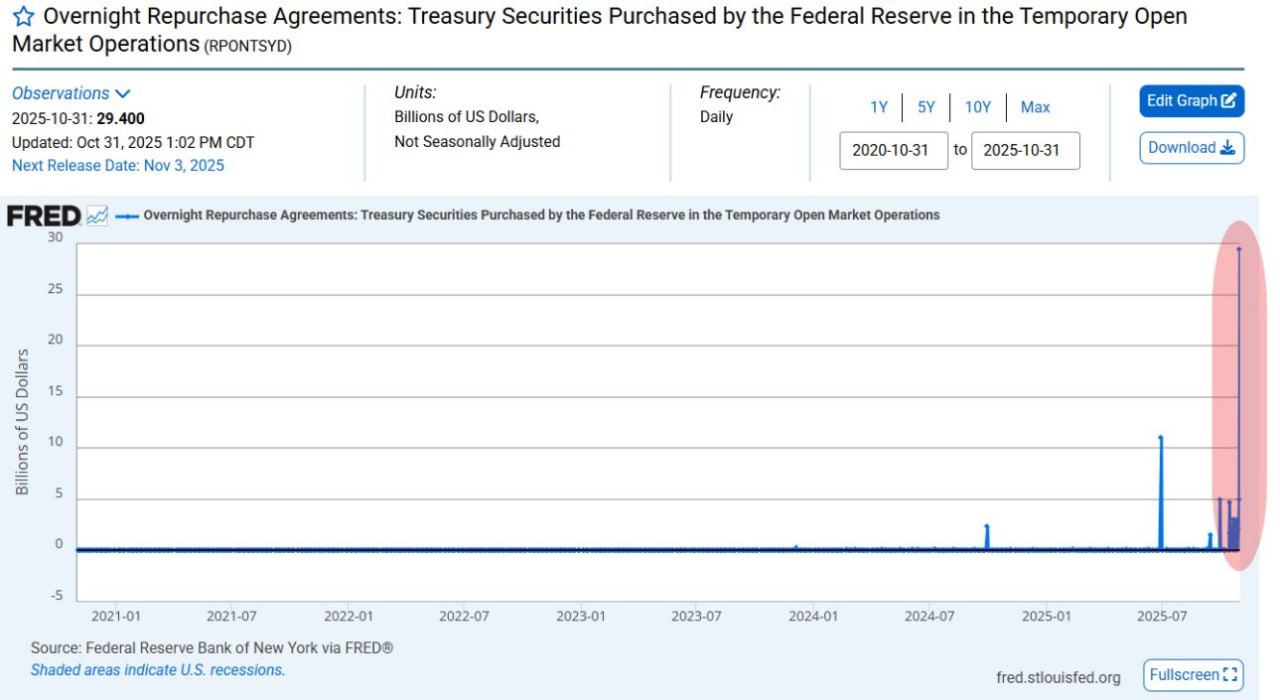

In November the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility (SRF) was tapped for another $30bn. This facility allows banks and primary dealers to borrow emergency cash overnight from the Fed.

Evidently, it was these key signals the Fed were watching that made them act, halting QT and now engaging in modest balance sheet expansion. The divergence in rates strongly suggested that reserves were becoming scarce at the margin.

We had expected this since Q3, the idea that reserves were below ample regardless of rhetoric from the Fed members stating that:

“Repo levels show we are at abundant reserves. A little above ample. We are starting to see tightening in money market conditions. Pace of run off is very slow. Not so far away now.”

- Powell in October

“The long stated plan has been to stop balance sheet runoff once ample reserves is met. Signs show this time is now.”

- Powell in November

Historically we highlighted in the Q3 report that the following causal events usually usually precede each other:

The Fed responds in a predictable sequence. It will first offer repo operations to inject temporary liquidity and smooth funding pressures.

Once stress persists, the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) will provide a backstop against disorderly funding conditions.

If the underlying issue becomes more structural, the problem becomes reserve scarcity rather than a temporary dislocation. In this case the Fed begin Treasury bill purchases to rebuild reserves on a more permanent basis.

These actions are not intended to stimulate risk-taking or ease financial conditions broadly. They are instead designed to keep short-term funding markets functioning smoothly and to prevent small liquidity mismatches from cascading into systemic stress such as what occurred in 2019. This is also why the Fed never announces such measures during periods of obvious excess liquidity. Technical balance sheet expansion only appears when reserves are approaching the lowest comfortable level for banks and the margin for error in money markets becomes narrowed.

To summarise, the interventions are less about monetary policy in the traditional sense and more about maintaining the integrity of the financial system’s operating framework.

Treasury Issuance Holds The Key

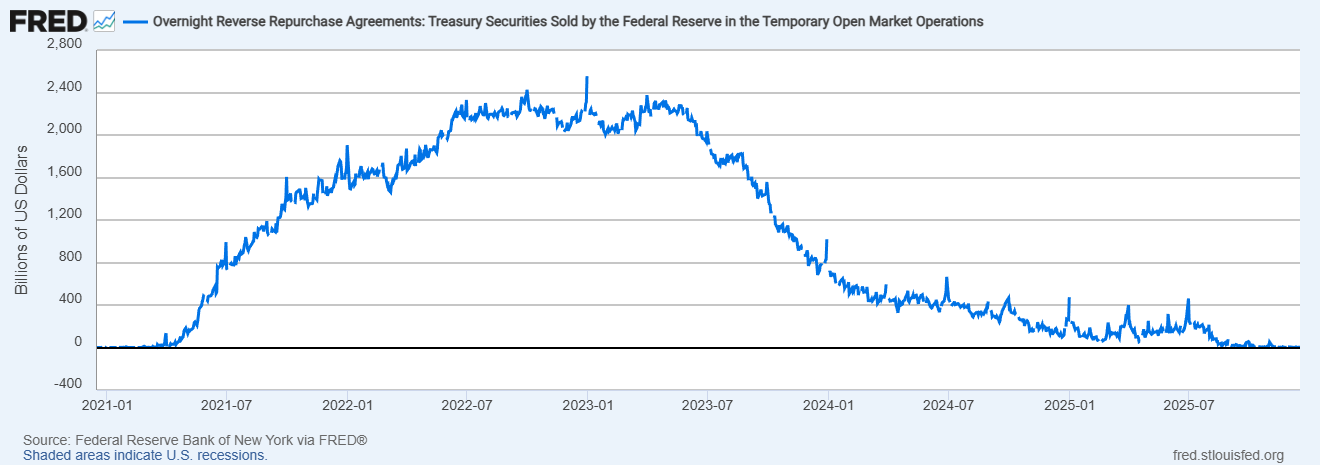

We have been talking about “Treasury QE” for over a year now. Since the market bottom in 2022, the Treasury first under Janet Yellen, then under Scott Bessent have been actively skewing supplying more bills to the market than usual. This created a huge boost to overall global liquidity. More bill issuance in general is liquidity-positive for markets, and was working well until the Reverse Repo Facility became empty over the past couple months.

In a general sense, when the Treasury issues more bills, no new reserves are created. Money market funds and banks purchase those bills using existing cash, which flows out of the banking system and into the Treasury General Account at the Federal Reserve. As a result, bank reserves decline…However slewing treasury issuance toward bill over the past 3 years was a net positive liquidity impulse for assets because bills were brought by money market funds using cash parked in the reverse repo facility. This drained “sterile” liquidity without reducing bank reserves. Cash sitting in the RRP couldn’t circulate or support leverage, but once it moved into T-bills it re-entered the market as usable collateral, boosting repo activity, balance-sheet capacity, and USD funding globally - hence the run up in equities. This is the key distinction.

At the same time, Treasury bill issuance is liquidity-positive for funding markets because it increases the supply of high-quality collateral. Treasury bills are the most desirable form of collateral in the financial system. A larger supply of bills improves the functioning of repo markets by increasing available collateral, tightening spreads between SOFR and the policy rate, reducing the cost of repo financing, and easing funding stress.

Once the Fed’s bill purchases are NOW added to the picture, the combined effect becomes more straightforward:

Treasury issuance increases the supply of collateral but reduces reserves (now that the reverse repo facility is empty).

When the Fed then buys those bills, it replenishes reserves by creating new ones, while leaving the duration profile of the market largely unchanged.

Together, these actions raise collateral supply and reserve balances at the same time.

Repo market functioning improves, overnight rates remain anchored, and money market stability is relatively preserved.

Treasury issuance alone is collateral-positive and reserves-negative.

Fed purchases alone are reserves-positive and largely collateral-neutral.

Combined, they are net-liquidity-positive and stablising for front-end funding markets.

This interaction proves the Fed and Treasury are deeply in cahoots with one another. We should also mention that the credible announcement itself of regular bill purchases also has immediate pricing effects. When the Fed commits to buying bills every month, market participants know there will be a steady, price-insensitive buyer at the front end. Bill yields compress and dealers alongside money market funds gain confidence that short-term paper can be readily offloaded to the central bank. A de facto “Fed put” emerges in the bill market.

However, this strategy cannot continue indefinitely without consequences as we made clear in the Q4 report (https://labyrinthcapital.co.uk/financial-reports/p/2025-q4-report-12000-words) . Increasing reliance on bills shortens the government’s maturity profile, raising rollover risk whilst increasing sensitivity to short-term interest rates. It shifts the investor base away from pensions and insurers, which prefer long-duration assets, and toward banks and money market funds. As rollover intensity rises (which is coming in 2026), the system becomes increasingly dependent on Federal Reserve backstops such as repo facilities and bill purchases to maintain orderly funding conditions. So in plain terms, the shorter the Treasury’s debt structure becomes, the more fragile the system is and the more it relies on the Fed to keep short-term markets functioning smoothly.

The Baseline Pace

Powell mentioned the following:

“Reserves need to be constant vs the whole economy - requiring around $25bn per month.”

Here we can establish the “baseline pace” of balance sheet expansion. What this is describing is the amount of non-QE growth required to maintain an ample reserves regime. This growth is needed to accommodate the rising currency in circulation, expanding nominal GDP and payment flows. This is money creation, but it is slow, mechanical, and non-stimulative. It is fundamentally different from “True QE”, which aims to ease financial conditions by removing duration risk and compressing term premia.

This then explains why the Fed must grow its balance sheet over time “in line with the economy.” It is not a choice driven by asset prices or stimulus goals, but an actual structural necessity to prevent recurring money market stress in a system that is becoming increasingly reliant on short-term funding and central bank backstops.

Echoes Of 2019

We want to finish the primer with a recap of 2019 as it is the most instructive example of what’s unfolding and may eventually come. During this period we saw balance sheet contraction, followed by technically modest balance sheet expansion aimed at maintaining “ample” reserves and stabilising money markets, which then gradually grew into a larger and more persistent liquidity framework.

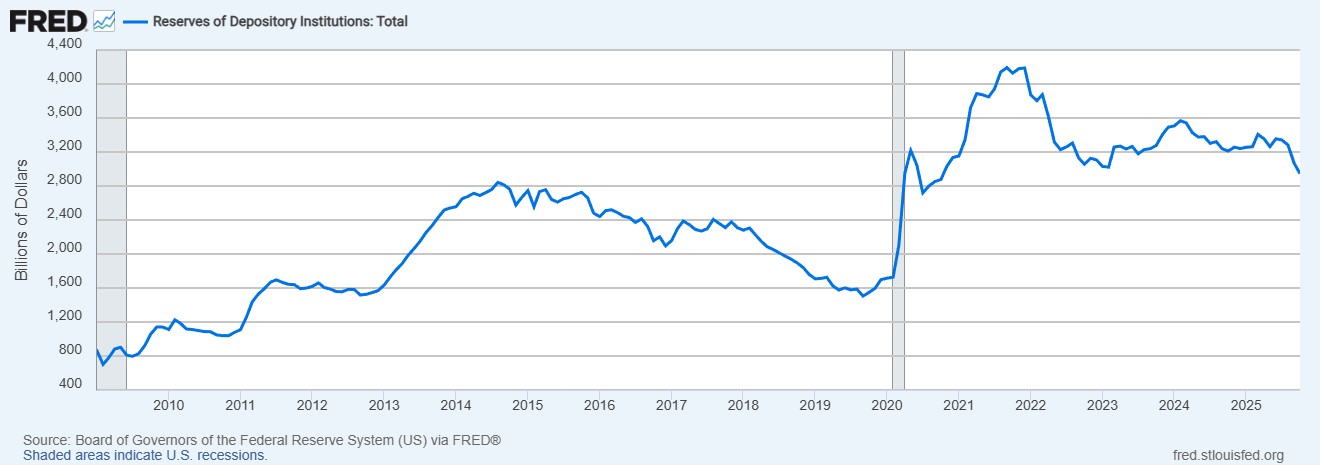

The backdrop in 2018 and 2019 was the Fed’s first serious experiment with QT. Between 2017 and 2019, the Fed steadily allowed assets to roll off its balance sheet, shrinking reserves in the banking system. Aggregate bank reserves fell from roughly $2.4 trillion toward what the Fed believed was still an ample level, though in reality the central bank did not yet know where the lower bound of comfortable reserves truly lay. The post-GFC regulatory environment had fundamentally changed bank behavior.

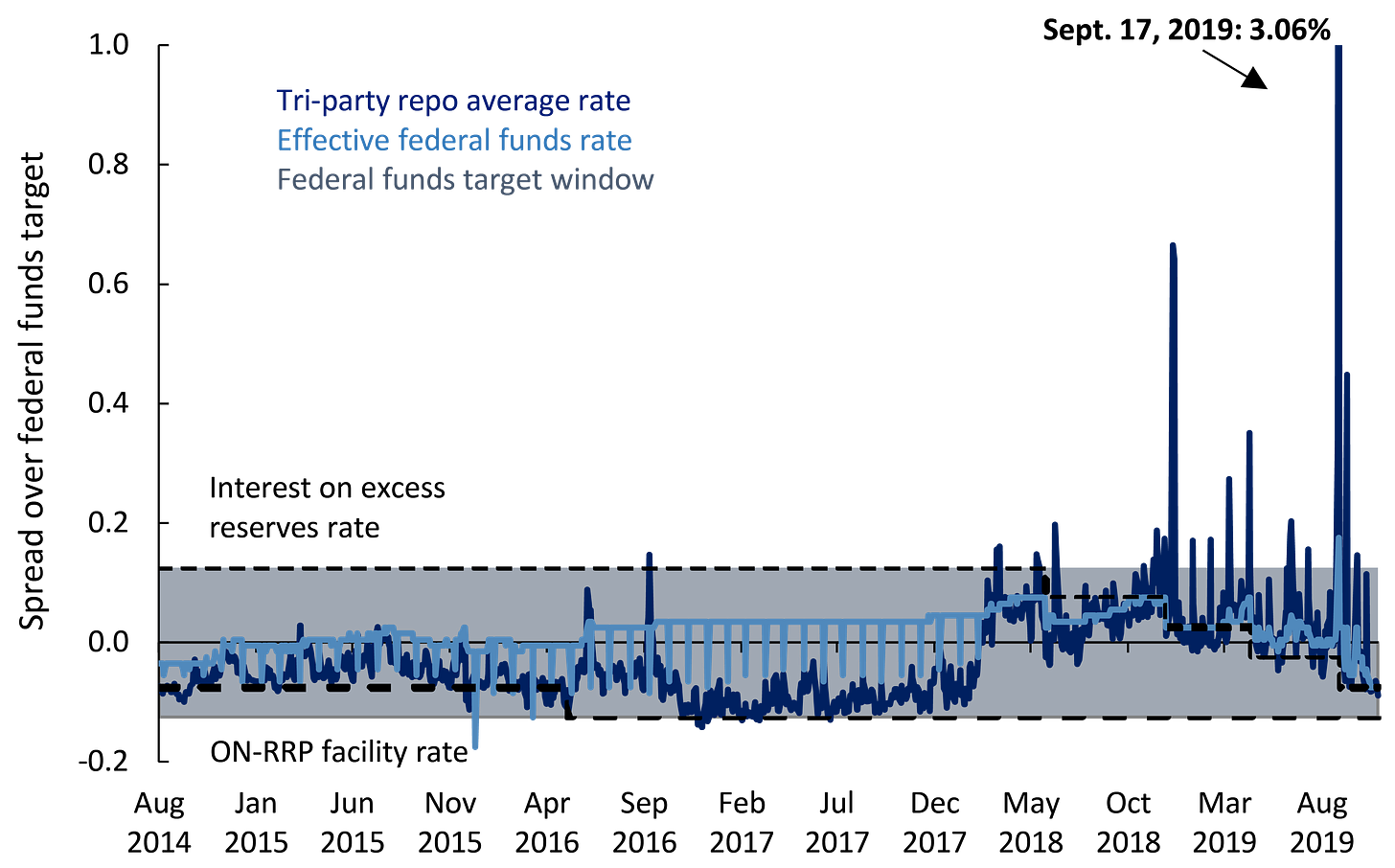

In September 2019 a confluence of events rapidly drained liquidity from the system when corporate tax payments pulled reserves whilst a large settlement of newly issued Treasury securities did the same. Reserves fell below what turned out to be the system’s minimum comfortable level, and the result was overnight repo rates spiking dangerously. The ratio of liquidity to collateral was out of sync. Money markets broke before policymakers fully understood where the threshold was.

The Fed’s response unfolded in stages. The initial reaction focused on temporary liquidity provisions as they began injecting cash through overnight and term repo operations to stabilise funding markets and prevent further dislocations.

The second step came in October 2019, when the Fed announced it would begin purchasing Treasury bills at a pace of roughly $60 billion per month. The explicit goal was to rebuild reserves and restore confidence in money market functioning. Crucially, the Fed was careful to emphasize that this was not quantitative easing. Officials framed the program as a purely technical operation designed to maintain an ample reserves regime. Purchases were confined to Treasury bills rather than longer-duration notes or bonds, precisely to avoid altering term premia or signaling a shift toward macroeconomic easing.

This distinction is directly relevant to today. The structure of the program, the choice of bills, and the stated intent are remarkably similar to what the Fed is now doing. In 2019, the bill purchase program did expand the balance sheet, but it did not function as QE in the traditional sense. It was only when COVID hit, that the Fed pivoted abruptly to “True QE”, launching massive purchases of longer-dated Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities totaling more than $3 trillion.

The parallels to today are clear. Once again, the Fed wants to ensure that reserves remain ample rather than scarce. Once again, the Fed is seeking to prevent money-market stress before it becomes visible in rates. And once again, the preferred tool is modest, short-duration Treasury purchases rather than aggressive long-term asset buying. If reserve demand rises further or fiscal deficits continue to expand, the pace and size of these operations could increase over time.

There is, however, an important difference. In 2019, the Fed was reacting to an acute liquidity crisis that had already materialised in the form of repo rate spikes. Today, the Fed is acting preemptively. It should also be said that the SRF was not in place during 2019, so its likely without the SRF today, a 2019 crisis would have already occurred in overnight money markets. QT has reduced reserves, Treasury issuance remains heavy and balances at the reverse repo facility have become exhausted. The motive is fundamentally the same, but the timing is earlier.

Conclusion: Where to Next?

For markets, the distinction we have laid out is crucial to understand. Under the current framework, liquidity conditions can improve at the margin, but the structural forces that support sustained rallies in risk assets remain largely absent. This is why, despite the apparent turn in Fed liquidity, caution remains warranted as we look toward 2026 - particularly with the huge debt maturity wall coming due (detailed in Q4 report).

We should also mention a stark quote from Powell earlier this year:

“WE WOULD USE QUANTITATIVE EASING ONLY WHEN RATES ARE AT ZERO.”

Powell on Feb 11th 2025

What does this tell us? The Fed won’t shift to “True QE” unless rates are cut excessively to zero. Something to consider.

Join the Telegram Channel HERE

See our website for all quarterly reports: labyrinthcapital.co.uk